Us and Them

The story of Jesus’ encounter with the Canaanite Woman (Matthew15:21-28) that we hear this Sunday is one of the more difficult episodes of the

gospels. Not because it shares the opaqueness of many of the parables or

because Jesus is revealing a challenging theological truth. Instead, it’s

difficult to read and hear because it is a story about Jesus that doesn’t fit

our childish Sunday-school version of who Jesus was.

In this passage, Jesus has traveled to the Gentile

(non-Jewish) region of Tyre and Sidon. John the Baptist has been murdered by

King Herod (Matthew 14:1-12) and Jesus himself is now on Herod’s radar. It is

likely that Jesus has gone to these coastal towns to get out of Herod’s

jurisdiction and to have some time alone to grieve the death of John the

Baptist (throughout chapter 14 of Matthew’s Gospel, we hear, more than once,

about Jesus trying to find solitude for prayer and reflection). This would be a

region where he wasn’t known. And yet, he’s recognized by a Canaanite woman (a

Gentile) who comes to him begging for him to heal her daughter. But, even as a

non-Jew, she expresses faith in Jesus as she cries out Kyrie eleison—Have mercy on me, Lord. When others have called out

to Jesus with these words, he has acted quickly and decisively, offering

healing and wholeness (cf. Matthew 9:27; 17:15; 20:30-31). But in this

instance, Jesus doesn’t make any reply or acknowledge the woman at all—for the

first time, we hear about Jesus ignoring someone who asks him for help. The

disciples, of course, urge him to send her away. She’s calling after them and

is an annoying embarrassment.

|

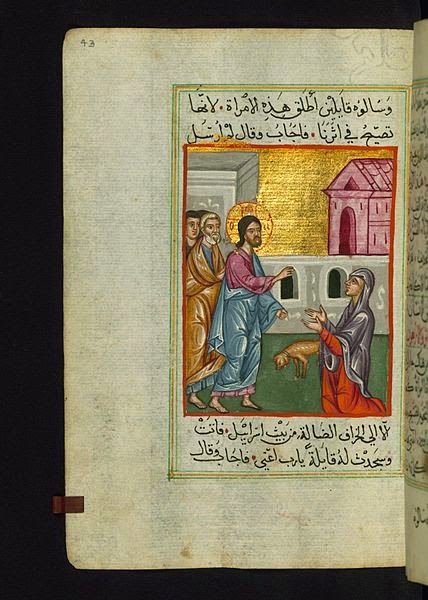

| Jesus and the Canaanite Woman by the Egyptian Scribe and Monk Ilyas Basim Khuri Bazzi Rahib (ca. 1684) in the Walters Art Museum |

The nameless woman isn’t put off by any of this. She’s

asking something for her tormented child and she shows a mother’s tenacity. And

when she calls out again, Jesus responds in a way that baffles and insults our

sensibilities: “It is not right to take the food of the children and throw it

to the dogs.” Although Scripture scholars have tried to explain this away,

sanitizing it by trying to give it cultural and historical nuances, it’s still

a shocking affront. But the woman doesn’t walk away, however hurt, angry, or

simply surprised she might have been. She uses Jesus’ own words against him:

“Please, Lord, for even the dogs eat the scraps that fall from the table of

their masters.”

Personally, I’ve always heard the woman’s words in a pleading

voice that reveals her desperation. It is how I imagine the prayers of those

who are desperate and with no recourse—the tone of those mothers who have sent

their children off into the deserts of Latin America, hoping they will find a

new home and life in the United States or those parents in Iraq who are weighed

down by fear and oppression, desperately seeking safety for themselves and

their children, away from religious fanatics bent on pillage, rape, and murder

in the name of our common God. It is the voice I’ve heard myself as I’ve stood

with families when marriages have failed or who have received a medical

diagnosis that can really only have one outcome.

But, perhaps that wasn’t how the woman responded at all.

What if her response was intended as a challenge to Jesus: “If you’re going to

call me a dog, then at least give me what you would give your dog!” This is the

same passionate defiance that Dylan Thomas expressed when he wrote, “Do not go

gentle into that good night, / Old age should burn and rave at close of day; /

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” The woman is, as Sister Barbara

Reid observes, stretching Jesus to “see her not as ‘other,’ or as an ‘enemy,’

but as one of his own, one with whom he shares a common humanity, a common

faith in God, a common desire for the well-being of children” (from Abiding Word: Year A).

This woman’s belief that Jesus is someone special, her trust

that he can effect a change in her daughter’s life is a powerful testament to

what is possible when we truly believe and stand firm in our prayer. She stands

firm in her request. What is it she understood about Jesus and his mission? We

will never know. But she placed her confidence in him and she wasn’t

disappointed. As the great theologian, Romano Guardini, reflects: “her own

heart is wide enough to understand [Jesus], her faith deep enough not to be put

off. That is the beauty of the incident. Quietly she accepts and uses the

humiliating metaphor; the Lord feels himself understood and loves her for it:

‘Because of this answer…’” He continues: “What comes from God does not

discriminate, qualify or limit, it overflows freely from his bounty. Here is no

philosophical system, no complicated ascetic doctrine, but the fullness of

God’s love, that divine audacity with which the Creator gives himself to his

creatures, demanding their hearts in return. Everything for everything; we

cannot but admit the truth of this—and in so doing pronounce our own judgment.

For are we any better than those others?” (from The Lord).

We Christians can be overly secure in our faith and in our

understanding of ourselves as children of God. But we owe this nameless Gentile

woman a debt of gratitude. The reason is because, like her, we are dogs at the master’s table

because we too are outsiders—we are the “them” to the “us” of Jesus and his

followers. After all, what made the woman an outsider and an enemy was that she

was a foreigner (non-Jew), a woman, and she’s annoying—she’s not pleasant or

easy to have around because she’s not respecting the established way of doing

things. Bu, her encounter with Jesus challenges him and we see something in him

begin to unfold. After all, earlier in Matthews Gospel, he had reminded his

followers that he had only come to gather together the “lost sheep of the house

of Israel” (10:6); It is only later that we will hear him instruct them to go

“into all nations” with the Good News (28:19). This story marks a turning point

for Jesus and his understanding of the saving mission that was entrusted to him

by the One whom he called “Father.” And so, for us outsiders, this story is an

essential part of our salvation.

There is another two-fold lesson here, I believe. First, we

have to be very aware of how we exclude others from our faith communities. The

Church has no place for an “us/them” mentality. Those walls have been broken

down: “For through faith you are all children of God in Christ Jesus… There is

neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not

male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). In many

of our communities we have a “saint versus sinner” mentality, or an idea that some

of us enjoy a certain “election” by God that excludes everyone else. Perhaps we

draw these lines based on race, gender, or sexual orientation (and this can be

done consciously or unconsciously). Others of us might be more hesitant to

embrace those of different socio-economic status (meaning both the poor and the affluent), those who are

divorced or remarried, the disabled, the mentally ill, those with a "history," or those with different theologies or political views.

If we discover that we are part of a faith community that has these prejudices,

we have to ask ourselves, “Who we are protecting?” Surely we can’t believe that

we’re protecting God or the integrity of the Gospel.

Second, we have to be willing to accept that this story has

consequences for how we engage the broader culture. There is no possibility of

our divorcing our faith and prayer from the demands placed upon us by the

broader culture. It is so easy to set aside the demands of the Gospel for

expediency and comfort. Too often, we have allowed ourselves to be convinced

that the value of the separation of Church and state means that we are freed

from the obligations of exercising our faith as we fulfill our civic duties.

Beyond this, we also have to risk the criticism, judgment, and possibility of

change that can occur when we speak out, in faith, for the rights of the poor,

the exploited, the sick, the persecuted, the homeless, refugees and migrants,

and all those others who live on the margins of our society. We Christians have

a responsibility to reach out to these individuals and groups within our

communities and this means risking going to the fringes ourselves to seek them

out and care for their needs.

As I said, if we had lived in Jesus’ time and culture, the

majority of us would also have been considered outsiders and enemies by his

first followers. We enjoy the spiritual comforts and assurance that we do

because of courageous women and men of faith who claimed their place as a

follower of Jesus. This is our inheritance and we do not have the right or

privilege to make a “them” of anyone else. God’s Kingdom is a place of welcome,

safety, and nurture to all, because all are invited.

Comments

Post a Comment