Who Do You Say That I Am?

The question Jesus poses to his closest followers in this

Sunday’s Gospel is one of the most essential in all of Scripture: “Who do you

say that I am?” For many of us today, this question has lost some of its power

to surprise and intrigue us. After all, wasn’t all that settled centuries ago?

|

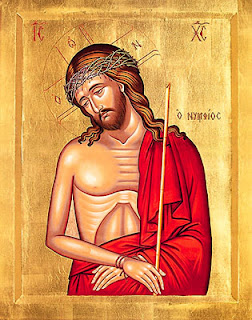

| Icon of Christ, the Divine Bridegroom |

If we only want to approach the question of who (or even

what) Jesus is from the perspective of orthodox, historical theology, then the

answer is yes—ecumenical councils and some of the greatest minds of the Early

Church worked to understand and explain Jesus’ relationship to the

Father/Creator, his place within in the Trinity, and the interplay of his human

and divine natures. The Catechism of the

Catholic Church (§423) sums it up in this way:

We believe and confess that

Jesus of Nazareth, born a Jew of a daughter of Israel at Bethlehem at the time

of King Herod the Great and the emperor Caesar Augustus, a carpenter by trade,

who died crucified in Jerusalem under the procurator Pontius Pilate during the

reign of the emperor Tiberius, is the eternal Son of God made man. He 'came

from God' (John 13:3), 'descended from heaven' (Jn 3:13), and 'came in the

flesh' (Jn 4:2). For 'the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace

and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father.

. . and from his fullness have we all received, grace upon grace (Jn 1:14, 16).

Beyond this sort of formal inquiry, however, the same

question that Jesus posed to Peter and the other Apostles is being asked of

each of us: “Who do you say that I

am?” At this level, formal doctrines and creedal statements can only form a

foundation or starting point for an answer.

The first generations of Christians came to understand who

Jesus was as they wove together their own experiences of Jesus of Nazareth with

the hopes and expectations of the people of Israel, embodied in the Law and

Prophets. That Jesus is the long-awaited Messiah (which was Peter’s answer, cf.

Luke 9:20) is something that Christians today both take for granted (even if we

don’t fully understand the significance of the title) and easily dismiss

because that Jesus seems too far away

to be accessible or approachable. Jesus, however, provides a sort of

reorientation when he reveals that he is not going to fulfill the expectations

of those who want a messiah who is a source of glory and restored power for Israel.

Rather, he tells them that he “must suffer greatly and be rejected by the

elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed and on the third day

be raised.” Jesus is Isaiah’s Suffering Servant (ch. 53) and the one of whom

the prophet Zechariah said, “They shall look on him whom they have pierced”

(12:10). But, Jesus says more than this: he does not promise glory to his

followers—he will, instead, die for the redemption of humanity—and anyone who

would follow him would have a share in that redeeming death and renewed life:

“If anyone wishes to come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross

daily and follow me” (Lk 9:23).

Christianity is not an idea. Instead, it is the shared,

lived experience of countless people of faith who have come to recognize the

presence of “God among us” in Jesus. Flowing from this is the truth that to

claim the name of Christian, is to profess Christ and follow Christ. To seek to

live a private sort of faith, without demands, is to be something other than a

follower of Jesus—it is to simply be an admirer. As Blessed John Paul II said,

“The correct profession of faith must be accompanied by a correct conduct of

life… From the start, Jesus never concealed this demanding truth from his

disciples” (Homily, June 21, 1998). Death

and life are the legacy of all of us who follow Jesus.

Comments

Post a Comment